The

Kiss of the Oceans – The Meeting of the Atlantic and Pacific - The Panama Canal

We recently heard President Obama,

in his 2013 State of the Union address, talk about the need for infrastructure

spending to spur job creation and the economy.

He mentioned the 70,000 failing bridges (scary!) in the US as an example

of why this needs to be done, and soon.

However, as important as maintenance and fix-up projects are, he offered

no grand vision of what REAL infrastructure projects might be, and what they

could do for the country.

When we look back at other times in

US history, we see that major infrastructure projects have had huge and lasting

effects on not only the economy, but also the hearts and minds of everyday

people. Not to mention the beneficial

impact on lives (and other, perhaps less sanguine, unintended - or at least

unforeseen - consequences). Initiatives

such as the 1825 Erie Canal (which almost single-handedly turned New York into

the Empire State, making NYC the country’s premier manufacturing location,

port, and trade center throughout most of the 19th century, and helped

open up the western territories to more rapid settlement); the 1883 Brooklyn

Bridge (which was a major impetus to the creation of Greater New York in 1898,

joining the here-to-fore independent cities of New York (Manhattan, etc.) and Brooklyn into

one extra-formidable city); the 1950’s inter-state highway system (which,

although having the ostensible military objective of making the country ready

to mobilize, if need be, to repel invasions, had the effect of spreading

population from the urban centers to the suburbs, and making our country the automobile-centric

society that we still are today, and changing forever the American landscape). There are

many other examples of major infrastructure projects, which reflected a vision

on the part of their creators about the direction our nation should be going – the

Hoover Dam, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) regional plan and rural electrification

project, the Trans-Continental Railroad.

Not all of these were strictly government-led and financed projects, but

all succeeded because of government support and encouragement in some way.

Some might say there is no place in

the world today for these grand gestures, no money to think about providing

today for benefits to the future generations.

Despite all the guilt-trip talk from the Republicans focusing attention

on our national fiscal responsibilities, and whether or not we want to saddle

our grandchildren with today’s debts, we seem unwilling to really think about

our legacy and responsibilities to the future.

What will future generations see about us, how will we be remembered as

a generation? Although this is not the main

reason we should move to do something, it is sad to think that our time will be

remembered for its high partisanship, gridlock, paralysis, intolerance, rejection

of good governance, and lack of clear direction. It is as though we are just muddling through,

from one crisis to another, with temporary quick-fixes and a band-aid approach

to solutions.

Some might also question the wisdom

of embarking on projects for which we don’t know the long-term impacts, and

certainly some of these past infrastructure schemes were ill-advised in terms of how they affected

significant portions of the population and, of course, the environment. Many of these infrastructure projects had/have

pernicious effect on the environment, with dams being the ultimate consumers of

land, highways hollowing out cities and enabling urban sprawl, and the invasive

spread of settlers via canals and railroads hardly benign to the landscape,

ecological health, or indigenous populations.

Hopefully today we have the wisdom gained from past experiences to try

to prevent environmental depredations and environmental injustices when

planning for major projects like these.

In a time when Tea Partiers and

Republicans in general (and not a few Democrats, too) believe that government

should be smaller, less obtrusive (except in regulating personal matters!), less spend-y, it is probably not the time to

contemplate major infrastructure projects, not even ones which might heal the

economy, boost the feelings of national confidence and pride, and provide inspiration

to the future. Everyone is too timid

these days to propose anything on a grand scale. This cautiousness will not stand us in good stead as we face the challenges of the 21st century - energy needs, global climate change, transportation, housing - which cry out for bold infrastructure planning and investing. But perhaps the days of big, bold initiatives are over. Maybe what we need is a

big, bold vision for lots of smaller projects that together can address the

issues. But without an organized plan to combine these projects into a meaningful solution, it will not work.

NASA

MODIS satellite image of the Panama Canal Zone (2003). White areas represent clouds, dense jungle

areas in green.

We are coming up on the 100th

anniversary of the opening of the Panama Canal, the “Kiss of the Oceans,” that

long-sought-after short cut between the world’s two largest oceans. America’s involvement in the project is

still controversial, and our continued occupation of the Canal Zone (until

1999) was surely a sore point in Pan-American friendships and dealings. Coming

on the heels of America’s 1898 empire building activities in acquiring/annexing

Hawai’i, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, plus briefly Cuba, the building and

subsequent ownership of the Panama Canal sealed American’s emergence as a global

Super Power. Despite the imperialistic overtones

of the US involvement in the Panama Canal, the creation of the Canal also represents some of

what is best about America – ingenuity, perseverance, and optimism in the face

of adversity.

Map

of the Canal’s major elements

There is a very nice interactive

map on the Panama Canal and all its innovative elements, from the PBS TV series “American

Experience.” The historic map used as

the basemap is a 1906 map of the Panama Canal compiled by surveys from the French and U.S. governments, and

was printed by the Millroy Publishing

Company of Dayton, Ohio, a copy of which could be “mailed to any address upon receipt

of 25¢”

New

Caledonia in Panama, the failed Scottish experiment in New World colonization and trade,

circa 1690.

The idea of the Panama Canal is a

very old one – first floated in 1534 by King Charles V of Spain, only a few

decades after the European “discovery” of the New World. It was recognized early on what a boon the

short cut would be to whomever could control it. And famously, it also inspired the doomed

Darien Scheme (alternatively referred to as the Darien Disaster). The Caledonia Colony was supposed to put

Scottish settlers on the isthmus, controlling the overland trade between Atlantic

and Pacific (similar to the Dutch East India Company's control of trade in Dutch colonies) in an immense

profit-making-turned-boondoggle - a project by the then-independent country of

Scotland. The subsequent abysmal failure

of the colony bankrupted the country through a kind of a burst financial bubble,

Ponzi scheme, and led directly to the necessity for Scotland to join in a Union

with England in the 1707 Act of Union, which created the United Kingdom. The Darien Scheme had bankrupted the nation,

by dissipating over 30% of the country’s total liquid wealth, and most of the Caledonia colonists died in Panama.

New Map of the Isthmus of Darien in America, The

Bay of Panama, The Gulph of Vallona or St. Michael, with its Islands and

Countries Adjacent, 1699.

In the 1860’s, the French got

serious about building a canal across Panama’s isthmus, after the success of

their Suez Canal linking the Mediterranean and the Red Seas, thus connecting

Europe and Asia by a shorter water route than shipping around Africa's Cape. After 8 years of set-backs,

including earthquakes, yellow fever, malaria, and floods, the French gave up on

the Panama Canal and left, and plans for a canal lay fallow for 15 years or

so. Eventually, the Americans picked up

the idea, and the design and construction of the Panama Canal absorbed some of

the best technological and engineering minds of the day. There were many geological, political, climatic,

public health, and technical impediments, and the struggle to complete the

canal took over 10 years. A good history

of all the engineering challenges, break-throughs, and triumphs can be viewed

at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/general-article/panama-engineers/

There are any number of good books

written on the engineering marvel that is the Canal, including David McCullough’s

1977 classic The Path Between the Seas: The

Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914; Julie Greene’s 2009 The Canal Builders: Making America's Empire at the Panama Canal;

Matthew Parker’s

2007 Panama Fever: The Epic Story of One of the Greatest Human

Achievements of All Time - The Building of the Panama Canal.

Being constructed in the early 20th

century, the thousands and thousands of workers needed to build the canal were

not treated according to today’s standards, turn-over was very high, and there

were severe disparities depending upon race.

Workers were divided into “skilled” or “non-skilled” labor, but those

were merely code words for white workers versus black, native, and asian. Many of the non-US and non-European workers

came from the West Indies, especially Jamaica.

To this day, many Panamanians can trace their ancestry back to Jamaica,

Barbados, and some of the other islands. In addition to discrepancies in pay, housing accommodations,

and food between whites and West Indians, the white workers routinely received

better health care during the inevitable disease outbreaks, although potentially

anyone could die (and did die) from smallpox, yellow fever, malaria, typhoid,

dysentery, and even bubonic plague. There

were also differences in the actual work assignments, with West Indians

primarily being assigned the hardest and most dangerous jobs, such as dynamiting,

and excavation, with the ever present risk of landslides. Due to their poor housing and food, West Indian

workers were more vulnerable to disease and injury, and had a significantly

higher death rate than their white counterparts. Suicide was also prevalent, as were deaths

from snakebites. At least 25,000 workers

died during the canal’s construction, most of them West Indian, and most of those,

Jamaican or Barbadian. There are some

good books written about the Canal’s labor force, such as Michael Conniff’s Black Labor on a White Canal: Panama,

1904-1981; Lancelot Lewis’ The West Indian in Panama: Black Labor in

Panama, 1850-1914; and Velma Newton’s

The Silver Men: West Indian Labour

Migration to Panama, 1850-1914.

Coup d'Etat, 1903

Coup d'Etat, 1903

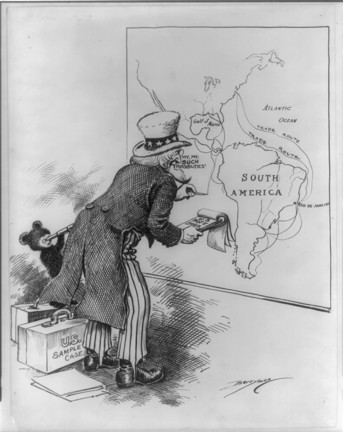

This cartoon portrays the intervention that Roosevelt and the US military undertook to support the Panamanian rebels in their

revolt against their Colombian overlords. In helping Panama achieve independence from Colombia,

the US received important financial and legal concessions in their negotiations

for building, maintaining, and profiting from the Canal. Note the gangplank "The Roosevelt Doctrine," which can be seen as an extension of, or a departure from, the Monroe Doctrine of the US objecting to intervention by European powers in Latin America.

The Canal, being seen as a very

costly (and “foreign”) endeavor, was not universally embraced by the American

people. Teddy Roosevelt, the Republican president

who spearheaded and championed the project, came under harsh criticism

throughout most of the construction phase.

Delays and cost overruns were rampant. Newspaper Cartoons that lampooned the project abounded.

Note the small "Teddy" bear with the telescope to the left of Uncle Sam, a well-known reference to Teddy Roosevelt. Uncle Sam is saying "My, My, Such Possibilities." Library of Congress

The President in Panama - The Washington Post. Note again the small Teddy Bear behind Roosevelt with the binoculars.

Roosevelt made a trip to the Canal Zone in

1906, however, and after his impressive speech to Congress, the tide turned,

and support from the American people was more forthcoming, and even became a

point of pride for decades afterwards. (See

what a difference an inspirational speech can make?) See a transcript of Roosevelt’s speech at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/primary-resources/panama-message/

Postage

Stamp commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Panama Canal. Note Yankee Clipper plane (carrying air mail) coming in for a landing.

The Canal was undeniably a force in

America’s ascendancy, the start of the American Century, and although often

viewed as just another instance of American Imperialism, it did indeed benefit the

entire hemisphere, and probably the world, in many respects.

By the way, some observant readers

may have noted that although the Canal was completed and opened in 1914, the Kiss

of the Oceans image has a 1915 date on it.

That is because this artwork was created for the 1915 Panama-Pacific

Exposition in San Francisco, California, which was meant as a celebration of

the opening of the canal, but with the additional alternate purpose of showcasing

the city’s revival after the 1906 earthquake.

Here is another example of a poster

related to the Exposition – it is advertising a flying-around-the-world competition

“under the auspices” of the Exposition. This one, interestingly, features one of

my favorite map projections, the Cahill Butterfly Projection. For a post on the Butterfly projection (and why I like it) see http://geographer-at-large.blogspot.com/2011/11/whats-your-favorite-map-projection.html

There were numerous

versions of the Kiss of the Oceans poster, here are just three more.

And here are a couple of great cartoons of the day, bashing the US's empire building and involvement in foreign "nation-building." The US was still in its isolationist phase, and popular opinion was large against the expansion of US territories outside the continent. As today, many celebrities and prominent people were against war and government interference in other nations' business (Mark Twain, for instance, was Vice President of the Anti-Imperialist League, as was Samuel Gompers, the labor leader, and Jane Addams, women's suffrage and world peace activist), and also as today, business and industrial interests won out.

As Waldo Tobler would say “Everything is related to everything else…..” And The Map Monkey is out to prove that, given enough time to meander, one can start a geography story on just about any topic (i.e. national infrastructure), and end up almost anywhere else (i.e., Panama Canal, Scottish New World Colonies, World's Fairs, Butterfly Projection, American Anti-Imperialist League).

And here are a couple of great cartoons of the day, bashing the US's empire building and involvement in foreign "nation-building." The US was still in its isolationist phase, and popular opinion was large against the expansion of US territories outside the continent. As today, many celebrities and prominent people were against war and government interference in other nations' business (Mark Twain, for instance, was Vice President of the Anti-Imperialist League, as was Samuel Gompers, the labor leader, and Jane Addams, women's suffrage and world peace activist), and also as today, business and industrial interests won out.

As Waldo Tobler would say “Everything is related to everything else…..” And The Map Monkey is out to prove that, given enough time to meander, one can start a geography story on just about any topic (i.e. national infrastructure), and end up almost anywhere else (i.e., Panama Canal, Scottish New World Colonies, World's Fairs, Butterfly Projection, American Anti-Imperialist League).

[This post is dedicated to my Dad (Daddy-o) who often spoke about the 7th Wonder of the Modern World, the Panama Canal, and always said one of the highlights of his life was traveling through it and experiencing it first-hand. He was born in the year the Canal was completed, and would have celebrated his 99th birthday this week.]

No comments:

Post a Comment